The health gap between more and less advantaged people persists in many countries and settings around the world, including the UK and Scotland. There is masses of research on these health inequalities. We understand that they are caused by systematic differences in access to things like a good education, good and consistent employment, reasonable income level, a safe physical environment and participation in supportive social networks.

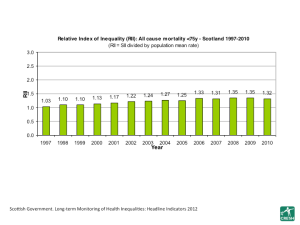

We know what the problem is, but we don’t seem able to tackle it. The graph below, for example, shows the slow, steady increase in inequality in mortality rates in Scotland over time (the taller the bar, the worse the health inequality). There is no sign of any real progress, at least using this relative measure. The graph is taken from here

One solution often proposed by health inequalities research is to create a better, more equal world; the WHO’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health recommends, for example, that we “tackle the inequitable distribution of power, money and resources”. This echoes many calls in the literature, including our own, for reduced income inequality and more equal opportunity, at the population level.

We believe that attaining a more economically equal society would be the most powerful way to equalise health, and that all health professionals should continue to agitate for it.

However, we also believe that there is no real sign or prospect of this happening to the degree needed to really reduce population level health inequalities. Our sense is that the actions suggested by health inequalities research seem outlandish to politicians (at least those with a realistic prospect of power), to policy makers and, importantly, to the public. Plus, those who already have relatively more wealth have a vested interest in protecting their position and do so vigorously.

The British Social Attitudes Survey , which has long questioned people about their attitudes to the income gap between rich and poor, supports our rather negative perspective. Here’s a graph of the BSA data showing the long term trends in concern about the income gap, and support for redistribution. The graph comes from here.

Now look at the recent shifts in attitudes to tax and spend.

So, the majority of people are concerned about the income gap and this has been the case for a long time. Yet far fewer want action on it, and there have recently been sharp falls in support for more tax and more spending. Perhaps most damning is the fact that just 5% of the respondents to the 2012 BSA survey saw extra government spending on social security (the key lever by which redistribution might occur) as a high priority.

We don’t think health inequalities researchers should call for macro-scale redistribution of income and opportunity as the only solution to inequalities when it seems highly unlikely that such changes will actually happen any time soon. To do so is a bit like telling the patient they need a pill that isn’t available yet. Of course, we should not stop trying to make that pill real, but we must also try to do something about the health gap now.

Not all health inequalities research proposes that this macro-scale economic change is the way to narrow inequalities. The big growth in ‘intervention’ research represents a growing desire to tackle health inequalities by finding out ‘what works’, using higher quality experimental or quasi-experimental study designs to do so. A problem with this route to tackling population level health inequalities, however, is the trade-off required. In intervention research we trade down the scale of our work (in time-span, population covered etc.) in return for a study design that can demonstrate causality. Interventions also often only seek to pull one lever to try and affect health, and we know that the causes of population health inequalities are multiple and macro scale. It is hardly surprising then, that many interventions do not narrow inequalities within their study populations and some actually increase them. Furthermore, for any intervention study to have meaning for population level inequalities, we rely on the idea that the effective intervention can or will be rolled out at the necessary scale. The irony is that, with better study designs, we are now more certain than ever before about what doesn’t work to narrow health inequalities.

There is, therefore, a quandary for inequalities research. The macro-scale social and economic changes we think would narrow population level inequalities seem unlikely. The meso/micro-scale interventions we test are either too narrow, don’t work or are unlikely to be rolled out

So, is there a way forward? To narrow inequalities in health we need to affect the lived experiences of everyone, every day. We know that the places people live contribute a huge amount to their identity, behaviours and characteristics. Neighbourhoods are, in effect, like fields in which we grow lives, rather than crops. Perhaps ‘place’ is one way we might think differently about health inequalities. Existing research already hints that the conversion of socio-economic inequality to health inequality varies from place to place. Some places seem to foster narrower health inequality from a given level of socio-economic inequality.

We hypothesise that some features of the social, physical or service environment could act to create health equality. It is important to understand this would not be because the socio-economic gap within such places is narrower. It would be because the conversion from socio-economic inequality to health inequality is weakened somehow. With apologies to Aaron Antonovsky, we have coined a name for this process; equigenesis. We think that focusing on equigenesis would be a valuable addition to thinking and research on how to narrow health inequalities.

Equigenesis might work in two ways; levelling up or levelling down. An equigenic environment which levels up presumably supports the health of the less advantaged as much as, or perhaps more than, the more advantaged. An equigenic environment which levels down presumably limits the health of the more advantaged to a greater extent that the less advantaged. Given our desire to improve population health overall, it would clearly be better to level up.

Is there any evidence which hints equigenic places might exist? For a place to be labelled equigenic, it would need to have a sustained record of narrow or narrowing inequalities over time; few studies have looked over time at variation between populations in the health inequality stemming from a given socio-economic gap. However, data recently released in the UK showed considerable variation in the trajectory of occupational class inequality in mortality between Government Office Regions. The North East of England experienced a large fall in mortality inequality, whereas the East Midlands experienced a small rise. Inequality went down in the North East because mortality rates fell faster among the least advantaged than among the most. This is a hint that something about the North East is equigenic, and that it is levelling up.

The idea that specific environmental attributes might foster narrower socio-economic health inequalities was also touched on in our 2008 study suggesting that income-related health inequalities were narrower among residents of neighbourhoods with more green spaces (such as parks and woodlands). The hypothesis was that greener neighbourhoods provided equal access to a resource for health and wellbeing. In less green neighbourhoods, access may have required material resources or transport.

So, whilst we work towards a more equal distribution of power, money and resources, finding and understanding populations which already have a sustained record in narrow or narrowing socio-economic health inequalities might help. In proposing the term equigenesis, we are asking a question. Can places make us more equally healthy? What features of places might be equigenic?

4 thoughts on “What is equigenesis and how might it help narrow health inequalities?”